NFT IP: Exploring the Brave New World of Non-Fungible Tokens and the Outer Limits of Intellectual Property

Representing what is perhaps the most cutting-edge new investment phenomenon of this past year, non-fungible tokens are the new crypto craze, just a short five years after most of us started learning about Bitcoin, Ethereum, and the various ‘alt coins’. Of course, with new technological developments arise a host of novel legal issues, stretching the limits of traditional intellectual property law. Hence, this brief survey of the still-nascent NFT relative to existing IP.

Copyright

Copyright is perhaps the most relevant and well-established form of IP protection relative to NFTs thus far. Under U.S. law, copyright exists in the underlying work if it’s considered an original work of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression. For instance, paint arranged on canvas could be considered a copyrightable work. However, minting the same as an NFT simply encodes the data on the blockchain as an electronic certificate of authenticity and automatic, smart contract.

Specifically, the NFT is not protected by copyright as it’s simply encoded data. So the purchaser essentially owns just a link to the artwork but not the underlying copyright, unless it’s specifically included in the sales agreement, as one finds on the Mintable platform. For instance, CryptoKitties licensees may commercialize their NFT with an gross revenue cap of $100,000 per year.

Unfortunately, as the purchasers discovered in the recent ‘Dune’ fiasco, buying a rare book for three million dollars with the intention to then mint and sell portions as NFTs is simply not permitted under copyright law though.

In fact, on most platforms, the purchaser can only sell or transfer the NFT to others while the author reserves all rights in the underlying work, including reproduction rights, public display rights, distribution rights, and rights to derivative works. However, as discussed below, sometimes contract law takes precedence over copyright. Meanwhile, minting rights belong to the author unless they’re licensed or the work in question is commissioned or made for hire, as defined in the Copyright Act.

Finally, copyright infringement raises some interesting new issues in the NFT space as minting is simply data encryption rather than copying. So tort law actions, such as misappropriation, passing off, and unfair competition could be more relevant in such cases. DMCA takedown notices are still effective tools in this context though as recently seen when CryptoPhunks attempted to capitalize on the popularity of CryptoPunks by offering nearly identical images. Furthermore, as explained below, trademark infringement could potentially be raised in such instances.

Contract

One good example of contract taking precedence over copyright is the recent Miramax v. Tarantino case. Essentially, this is a contractual dispute over the movie “Pulp Fiction” and the minting of NFTs, and the written agreement between the respective parties should supersede any copyright considerations since all copyrights were granted to Miramax in the parties’ original agreement.

However, Tarantino reserved rights for the “making of” books, comic books and novelization, in audio and electronic formats” as the most relevant ‘carve out’ provision. Of course, NFTs didn’t exist some thirty years ago, so contractual interpretation will turn on the above clause. While NFTs could arguably fall under “electronic formats” his NFTs would likely need to take the form of “books, comic books or novelization”, and it’s questionable whether the annotated scripts he’s offering would fit any of those narrow categories.

In the future, parties will surely include NFTs and maybe even some blanket language covering “new technologies”. But based on the verbiage above, it seems Miramax should prevail, while Tarantino will likely be able to offer future NFTs limited to these three specifically-enumerated categories.

Trademark

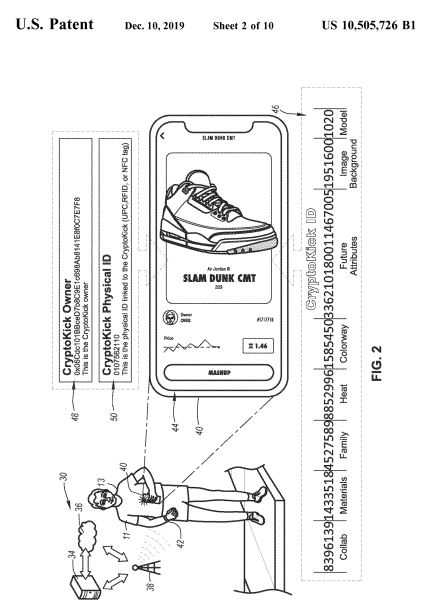

Probably most clear-cut of all, under existing case law relative to NFTs, is trademark. For instance, Nike has recently brought suit against StockX for minting NFTs based on physical products, including unauthorized use of the Nike name and logo, without the consumer even taking possession of the actual goods.

Likewise, just a month earlier, Hermes filed for both trademark infringement and dilution against an artist who started minting fashion handbag images as NFTs, under the MetaBirkins brand, ostensibly for use in the burgeoning metaverse. Meanwhile, the artist raised a First Amendment defense, likening the work in question to Warhol’s pop art, setting up an interesting test case.

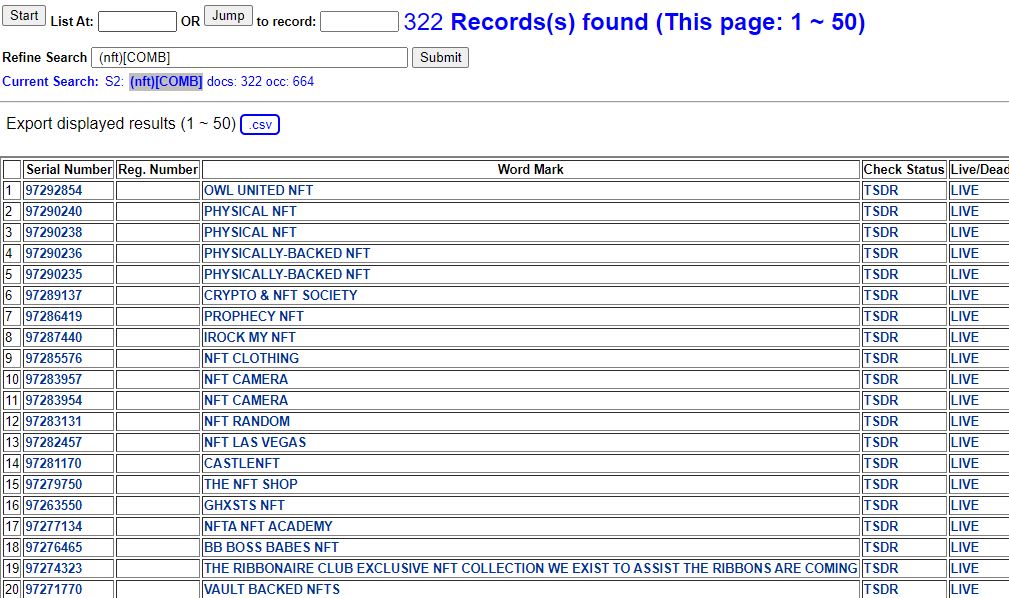

Arguably, while corporate brand owners could claim natural zone of expansion, many are now making it a point to apply for downloadable virtual goods and online retail store services featuring the same, in connection with their famous trademarks. In fact, since mid.-2021, there have been over 300 USPTO filings featuring “NFT” as a trademark element, typically under International Class 009 for downloadable software and digital media, Class 016 for collectibles, Class 035 for online marketplaces and retail store services, Class 041 for entertainment services, including virtual environments, and Class 042 for non-downloadable software and platforms. Although these applications are still pending review, within the next few months we’ll begin seeing various approvals and refusals.

Done properly, future creators would simply obtain trademark licenses prior to releasing their tokens. Likewise, brands could license their names and logos to consumers purchasing authorized, exclusive digital content in the form of NFTs.

Patent

Finally, patent law represents the least-developed area for NFTs but with limitless potential. Nike is currently in the forefront having registered digital versions of its products with the USPTO. So this will likely become a popular strategy for others as well in the months ahead, as long as the subject matter is considered eligible for patent and the invention is useful, novel and non-obvious.

In fact, IBM just recently announced its plans for a blockchain-based patent marketplace. Companies like IBM will be able to license their patent portfolios online, simplifying access through Internet availability, while reducing transaction costs via smart contracts.

However, this could also raise a host of new legal questions as existing case law is based on written license and assignment documents, highly-dissimilar from smart contracts. In other words, if traditional agreements are unavailable in such cases, how would inventors prove rightful ownership in the underlying patent should theft of the associated NFTs occur? Again, the courts and Congress will likely resolve such issues over time.

Just as we’ve observed some thirty years ago throughout the growth and widespread acceptance of the Internet, in the NFTs realm there’s currently a bit of a “Wild West” mind set. Courts are now retroactively attempting to fit this new technology within the framework of existing IP case law. Specific legislation will also likely be introduced as we’ve seen in the past with the advent of other new technology and innovation. Meanwhile, enterprising businesses and individuals will continue testing the boundaries of what is legally-acceptable in this rapidly-emerging digital frontier.

Originally published on BloombergLaw.com